About the Artist - About the Art

About the Artist

My eyes were permanently turned skyward with the launch of Sputnik, and my life (and neck) have never been the same. Combining this lifelong love of the stars with another interest, art, led to recognition in the specialized field of space art. My work has since been widely exhibited and published. Notable magazine contributions include art for Sky and Telescope’s pre-launch articles on NASA’s Voyager and Galileo planetary missions (including cover art), along with that magazine’s cover art of the Voyager 2 encounter with Uranus. One of my illustrations for National Geographic was among the images selected from that esteemed publication for major presentation in The National Geographic Society: 100 Years of Exploration and Discovery, a book celebrating the Society’s centennial—the only space art so honored. Other publication credits include Popular Science, Omni, World Book, The Planetary Report, Scholastic Weekly, Sterne und Weltraum, Geo (both Germany), Kijk (Netherlands), and Equinox (Canada) and several feature story and cover illustrations for Astronomy. When not engaged in the glamorous, grueling and dangerous demands of international space art, I relax by listening to music and I probably know more about opera than any sane person would care to admit.

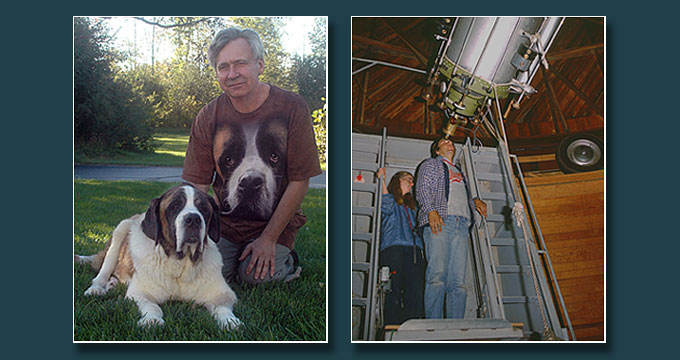

LEFT - With my BFBFF--Big Furry Best Friend Forever-- Olie (2006-2016). Miss him. Olie didn't have a lot to say, but when he did bark, the ground shook. When my own time comes, I'm putting in for a caretaker assignment in Dog Heaven (if they'll have me). I'm equally uninterested in the other options. Photo: Janet Riley

RIGHT - "Jupiterstruck". Back in 1984, taking in my best view ever of the big planet through the 24-inch Clark refractor at Lowell Observatory, probably my favorite place back here on Earth. Photo: Kim Poor

About the Art

When I first combined my astronomy and art interests in any kind of serious manner back in the the early 1970's (I'm self-taught in both fields, by the way), I worked with oil paint. I was slow to embrace digital art, but once I finally learned, I found working with Photoshop was immensely better suited to what might be called my "style".

I put "style" in quotes because I'm not sure I even have one. I do strive for hard-edged realism, detail and, in selective cases, scientific and technical accuracy. I was once told, however, that there isn't much "me" in my work. I took this to mean that while my work achieved some fidelity to its subject, it wasn't overlaid with much stylistic commentary by me on what was being depicted. I was inclined to agree (to an extent), but never really gave it too much thought previously. This prompted me to consider if (and if so, why) I prefer my realistic approach over one with more personal creativity.

First, I feel whatever appeal my work might engender comes largely on the strength of my subject matter itself, not any "interpretation" on my part. I don't think quasars, giant ringed worlds and humans setting foot on the Moon are subjects that need creative enhancement by me to be exciting. For the most part, I just try to realistically and convincingly depict the subjects. While the detail is a major component to this end, it is never just detail for its own sake.

As for the matter of technical accuracy, I have (somewhat reluctantly) found it necessary to be a bit flexible. While I will try hard avoid misrepresentation of the science, my research efforts, while extensive, are not exhaustive. At some point I have to stop searching out reference material to verify some scientific or technical esoterica and just work on the art.

I'm not a slave to absolute realism. I know that nebulae and galaxies don't really look like their big-telescope portraits, but depicting them as they would actually look from close range (rather dim and colorless in most cases) would make for pretty dull paintings. These aren't my favorite subjects anyway, but it's hard to resist their visual beauty as seen in their photos.

All this being said, I do think there is some degree of "me" hiding in my work.

In depicting Comet Donati, I showed it in the evening sky over the place of its discovery, arguably one of the most beloved cities in the world. Although the comet appeared at a time of political discord and upheaval in that part of the world, I envisioned a picture of quiet serenity with the graceful comet above a cityscape that is, itself, a work of art. My decision to completely omit any evidence of people in the scene was a deliberate one.

There is another particular scene in the gallery that represents an immense amount of research, detail, and much attention to accuracy. Yet, my inspiration to depict this place at this time in history arose from an emotional response to nature. Specifically, it's one of my favorite telescopic sights, one that occurs every month (sky conditions permitting). It's best in the spring, when the first-quarter moon rides high in the Northern Hemisphere sky at sunset. This is when the sun rises over the lunar Apennine and Caucusus mountain ranges that form the eastern boundary of the giant Mare Imbrium basin. At this time a remarkable sight occurs. The mountains (which actually have a relatively low, gentle profile) cast almost absurdly long shadows across the adjacent Imbrium plains. Further stretched by the Moon's curvature, some of these exaggerated shadows take on the sinister appearance of black daggers.

Whenever I see this on a steady night I think of the Apollo 15 crew looking out the spacecraft windows as they first glided over this same stark vista after their successful LOI burn. I always get just a bit of a chill seeing the mountains and those creepy shadows. However, it is one thing to contemplate them from a quarter-million miles away through a telescope, and yet another to strap yourself in a tin can and actually go there. I can scarcely imagine the drama and emotion of seeing this forbidding landscape from only fifty miles up.

I gave it a try in "Daybreak at Rima Hadley". I did not feel my own vision of the place and event could be achieved with a stylistic, painterly, personal approach. I instead sought to depict the scene (especially the rugged lunar landscape sweeping beneath the spacecraft) as realistically as my abilities would permit. I wanted to hold up a mirror to this monumental journey to this astounding place, without any further commentary on my part except, perhaps, to remind us all that fifty years ago we really did this.

Artists (and most everyone, I'm sure) like to think our work makes a little difference in the world. Some of my own satisfying recollections happened after one of my gallery showings and again after a talk on astronomy I gave to a local civic group. On both occasions after the events I was engaged in conversations with one or more attendees outside the facility. During these exchanges, I couldn't help but notice that as a few others would walk outside, they would put on their coats and then--seemingly without thinking-- glance up at the evening sky, look around for a second, and then proceed to their cars. Okay, maybe these were just the routine weather checks many of us do whenever we step outside, and not some subliminal influence of me or my art. But, hey, you have to at least give me this.

When your avocation is so often proceeded by the word "starving", you take whatever encouragement you can get.

- Jim